Paul Burch is something of a creative powerhouse with more than twelve album releases under his own name and others with such like-minded bands as The Waco Brothers. He has worked as a producer as well as a musician with numerous other acts such as Lambchop alongside his own WPA Ballclub comrades. He is also the author to the recently published novel Meridian Rising, which is a conceptual imaging of the life of the iconic country singer and songwriter Jimmie Rodgers. I have had the pleasure of meeting Paul on several occasions, here in Ireland, and always been captivated by his performance and personality. So, the release of his latest album, Cry Love and the aforementioned book provided a perfect opportunity to put some questions to him about his opinions and thoughts on related topics.

You were instrumental in bringing the ethos of traditional country and early rock ’n’ roll back to Lower Broadway in the early '90s. It was then considered a pretty rough area then that was to be avoided. Conversely, the same may be true of the area now for very different (often musical) reasons. How do you reflect on those changes in the area and beyond?

First, thank you to Lonesome Highway for welcoming me again. You're kind to offer me credit for helping to bring back some spark to Lower Broadway. But if I had any impact, maybe I should apologize. I went to see Elvis Costello at the Ryman this summer, and when I walked out after the show, I felt like I was in the film It’s A Wonderful Life when Jimmie Stewart’s character George Bailey goes to sleep in Bedford Falls and wakes up in Pottersville. Broadway was a rough area in my time, but there was some code among thieves. Today, it’s a fair reflection of how Western celebrity culture has gone amok. It feels like a deeply cynical place where everything—even your safety—has a price tag and the buyer has no value beyond the transaction.

When I came to town 30 years ago, Lower Broadway was so quiet at night you could hear the creak of the Ernest Tubb Records sign as it turned. Today, there’s no space between the notes. But sure as you give up on it, a true believer will emerge.

I have friends who knock around Robert’s Western World still. That hasn’t changed much. What’s really changed is that in most clubs, the musicians are told what to play. There’s no chance to harden your shell and hone your craft. I think musicians are at their best when it’s up to them to entertain whatever humanity the wind blows through the door. When we were down there, the music meant everything to us and the people who came to see us. That was our bond. But that’s the breaks. Like Col. Parker once said of Elvis: Nashville had a million dollars’ worth of talent. Now it has a million dollars.

You recently released a new album, Cry Love, with your friends and bandmates, the WPA Ballclub. The enthusiasm and pleasure of making music are apparent in the recordings. This is obviously still something that still inspires?

Yes, the WPAB still inspires me very much. This was a hard year for me personally, and the band was very sustaining. They are wonderful musicians and wonderful people—which I appreciate most of all. They seem to like what I write and trust me to keep them on their toes. And I trust that they’ll find the heart and soul of what I’m doing and help me make us something beautiful. They are gallant knights in my book. Something unique happens when we play together. They keep themselves turned towards the outside world, which is difficult for many musicians. We also share a love for recording live with no headphones, face to face. And there aren’t a lot of opportunities to do that typically. I hope they see the band as a place they can be themselves. When we’re on a roll, I don’t know an outfit anywhere that could cut us. And as Fats Kaplin has said himself: I’d like to see them try.

As a writer, singer, musician, and producer, you have added author to that list with the publication of your novel, Meridian Rising. Jimmie Rodgers is, I know, something of an iconic artist for you, so can you tell me something of the genesis of the book?

The genesis of Meridian Rising was gradual, mostly because I had no idea what I was doing, if I could finish it, or even how to get published. The big spark that led me to take up Jimmie Rodgers’ story again came when I read an interview with Howlin’ Wolf, where Wolf said as a young man he knew Jimmie and took yodelling lessons from him. I started to think of Jimmie as a town square where all my favorite musicians could meet. I also was inspired by how funny, bright, and self-aware Jimmie was. Meridian Rising became a musician’s On the Road. Musicians live a life flying low to the ground. They probably meet more people in their lifetime than any politician. You have to be quick-witted, forgiving, and self-aware to survive. As I got deeper into the novel, I thought the story could also give voice to my friends who make their living on the road. The difference I see between the album and the book might be that the album was for me—my personal adventure as a songwriter. Whereas the book was for Jimmie, the artist, and my artist friends. I don’t know if I was successful. But my aim was to show the value in being serious about what you love. Jimmie worked very hard. The best artists do.

In the past, I have spoken with some people who were known as songwriters who went on to write prose/ fiction, and they pointed out how different the disciplines were. How did you find the process?

The process found me. I knew the transition from writing songs to fiction would be awkward at first. But finding a place to start seems—in retrospect—harder than writing.

The only model I had was an interview Ernest Hemingway gave to the Paris Review in the early 1950s. Hemingway was in a charitable mood. I think he had just won lots of acclaim for The Old Man and the Sea. And he spoke about how a writer must set aside the same amount of time every day and write until they were almost empty. So, I tried my version of that. My discipline was writing at least 20 pages, double-spaced, for about two or three hours. Often, I had no idea what I was doing. But I kept at it, every day, and usually –sometimes even in the last 5 minutes when I couldn’t wait for the session to end--something would arrive in my imagination that made the other 18 pages work. Songwriting has a similar process, but overall is much sweeter and collaborative. For instance, you can have a rehearsal that’s absolutely shambolic. But you don’t have to relive it. Whereas no matter how good or bad your writing session is, you will have to read it again and spend hours fixing punctuation and adjusting sentences and all that stuff just to make it legible.

If you have a rough mix of your record, you can put it on in the background while you’re eating dinner and see if anyone notices. You can learn a lot about how you’re doing when you’re listening at low volume. But no one wants to read your unfinished novel. Songwriting also typically comes very quickly. I tried to imagine Meridian Rising as a long Irish ballad that didn’t have music. There are moments where other people in Jimmie’s life get to speak, looking back on their times together. Those moments were like being in a band where you give someone a solo. I may try it again, but at the moment, I’m relieved to be back in the world of music.

Will you continue in that direction, perhaps expanding the subject matter of your fiction?

I don’t know. If I can get lost again in a story with as much abandon as I did with Jimmie, I would write something else. I’d like to see some aspect of Meridian Rising go to film or stage. In songwriting, I try to write my very best for whatever situation I’m in. One time, a very big manager wanted to sign me to a label and asked me to write “10 more ‘Isolda’s” because he thought that was a song that could get on the radio. I told him I can’t do that. The one I wrote –for all its flaws and strengths—was about a particular time and place. Meridian Rising arrived during a special time and place. I still don’t walk around thinking that I’m an author. But if I get seized by an idea, I’ll try. There’s nothing wrong with just writing one good book. It seems like a lot of writers go mad if they keep at it.

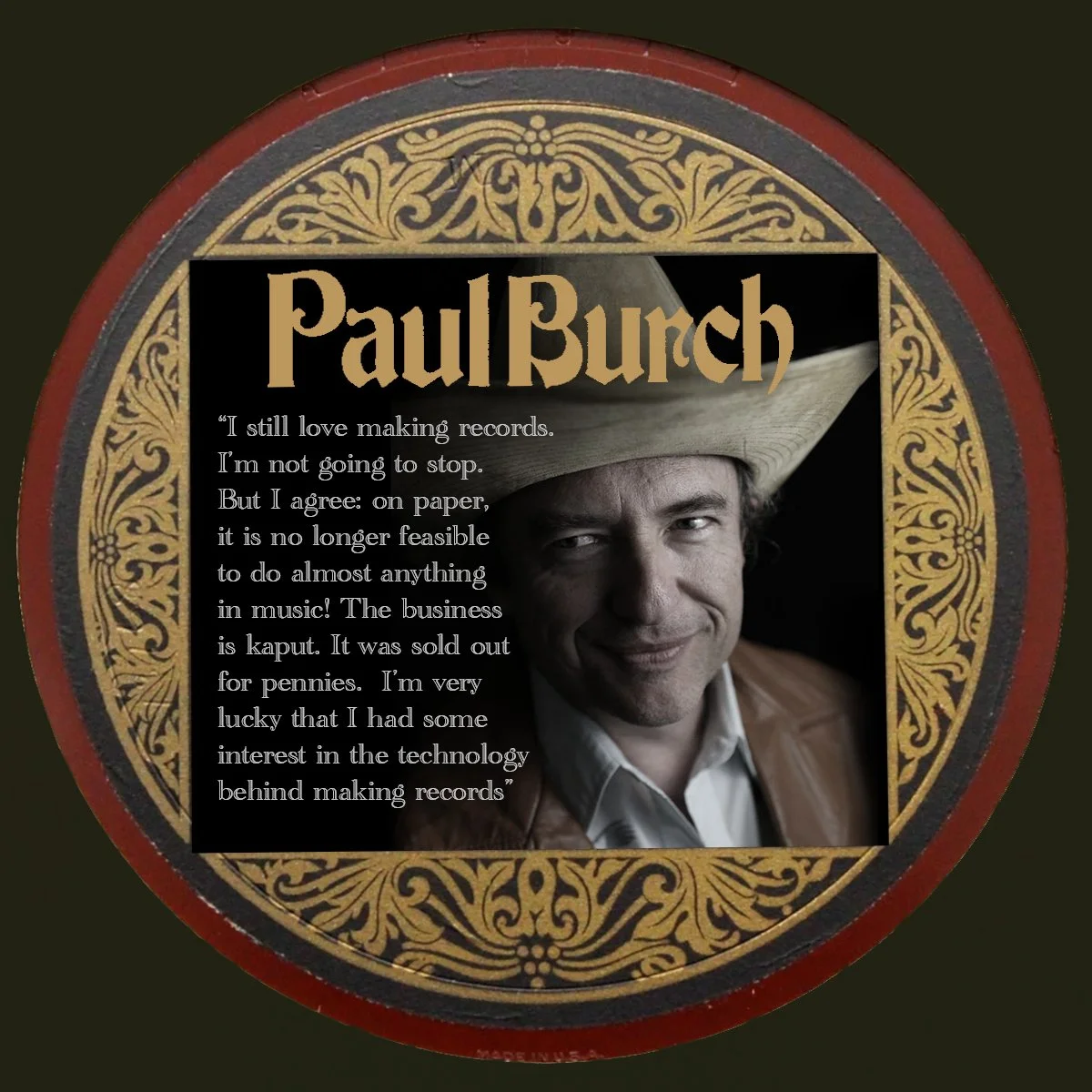

I have encountered some artists who are of the opinion that it is no longer feasible to physically release an album or even to record one, even though the process of home recording is more sophisticated these days. Where do you stand on that?

I still love making records. I’m not going to stop. But I agree: on paper, it is no longer feasible to do almost anything in music! The business is kaput. It was sold out for pennies. I’m very lucky that I had some interest in the technology behind making records. And since I’m in Nashville, I’ve had the help of a lot of great engineers. If I could afford it, I’d rather do most of my work in a proper studio. I still think a great studio and a great producer or partner is the ideal way to make a good record. There are a lot of good records out now that could probably be great records if the artist didn’t have to do all the work.

You have also worked as a DJ in recent times. Has that in any way changed your perspective on listening to music?

I love being a DJ. But like my music, the station I broadcast from, wxnafm.org, is very unique in that we can play what we want. My model, both in college and now, was to have a show like John Peel’s, where you might hear something made 90 years ago or something made last week. I’m not sure how it’s impacted my listening. I’m sure being a DJ has impacted my musicianship. I try to get to the point and get out, as John Lennon used to say. And that effort to be impactful has been informed by discovering a lot of music in the DJ booth. I tend to play artists I’ve never heard of before.

In these days of online listening and the seemingly vast amounts of music available to the casual listener, is this a good thing? In that light, I often think that a person like John Peel was a person you could trust to keep you in touch with good music from many different genres and understand where he was coming from without being elitist.

It's not terrible to have so much music available if you know what to look for. But for people who feel music deeply, I would imagine discovering new music is still a personal adventure they would like to see happen organically. No one likes to be told what to do or who to listen to. Peel and a few other DJs in the western world were really wonderful. They loved music and felt a responsibility to give artists a chance, whether they had any promotion behind them or not. I think kids in their teens and 20s are especially wary of the current industrial machine taking over their social life. It’s a new beat generation. They’re very aware that there’s a feeling of emptiness in almost everything. The baby boom generation is taking a very long time getting off the stage. But it just takes one or two great bands to come out who refuse to play the game. That’s what I’m counting on.

With the many changes in the way Music Row has and continues to function, do you find that Nashville is still a good base to work from?

I do. The musicianship and technical know-how are world-class. We’re all on the same life raft. There is still some funk left. I wish we could just all move to Memphis. I don’t think Nashville would miss us if the musicians left, frankly.

You were a frequent visitor to the UK and Ireland in the past. Do you have plans to return, or has the current travel situation led to a change in how the independent artist can tour, both abroad and at home?

I would love to tour more. Unfortunately, there just isn’t any demand or funds to do it. But if anything changes, I’d play as much as I could.

What are the sources you draw from to write, and do you do so regularly, and store material up, or is it best to write for a particular project?

Everything—truly. I’m not too conscious or specific about where I go for ideas. I still love bookstores, record shops, and drawing and painting. I don’t feel the pressure to be in the business. But I do have a small seat at a big table and I still love the company of people who—like me—are making records and recording. I still get a thrill out of releasing a new record and starting one—whether it’s mine or a friend.

You have been doing shows with the WPA Ballclub and introducing guests and having people join you onstage. How appealing is that open-ended, unscripted process?

I love it. I enjoy a set list—I’ve got nothing against them. But I learn the most by having some element of a show be unscripted. If you’re on the road, it’s important to have some structure not only for your peace of mind but for all the people working on your behalf. It’s a great feeling to see a good set list get better and better over many shows. When we play close to home and it’s more casual, it’s more fun and educational to see what happens when you can shake things up a bit. Often, I realize the artists I love are full of surprises once you get them on stage.

What are your plans for the next couple of years, or do you think that far ahead?

I do tend to think a little bit ahead. I have a number of songs that are profiles of people or places and at that moment-that feels like a very natural album. When the paperback version of Meridian Rising comes out, I’d like to re-release a shorter version of the album on LP but perhaps add some new instrumentals—perhaps read from the book, too. Fats Kaplin and I have a lot of instrumentals that would make a nice album. So yeah—it seems like I do think far ahead! But I’m also open to being surprised. Our time is finite. And there’s no time for waiting around anymore.

Is there any other course in life you could and perhaps would have followed in different circumstances?

I never wanted to do anything other than make records. I feel like my life overall is miraculous, and my ability to make music is miraculous. I’m a musician who probably wouldn’t impress anyone if I were just noodling on my own. But I come to life when I’m playing with good people. So, I’m very thankful that the few things I can do ok managed to attract –even for a moment—the great people in my musical life.

What have been the events and people that have stood the test of time for you?

There are so many. I’m not sure I can answer that very well. Coming to Nashville at the behest of my friends certainly changed my life. I was with my wife Meg for 25 years, and she passed away from cancer in January. That loss will reverberate and echo without end. As a musician, it’s probably pretty common to say the small events stand out the most. If I hadn’t met a particular person or gone to a particular club on the right night at the right time, my life could have taken a very boring turn or no turn at all. You know, Ralph Stanley didn’t find the audience he deserved until he was in his 80s. John Prine became a superstar in the last decade of his life. At some point, you have to trust that your work will lead you where you need to go and where you deserve to go.

Interview by Stephen Rapid and photography by Chad Cochran